Interview with Howard Brodie

.jpg)

John Turner OHS '65

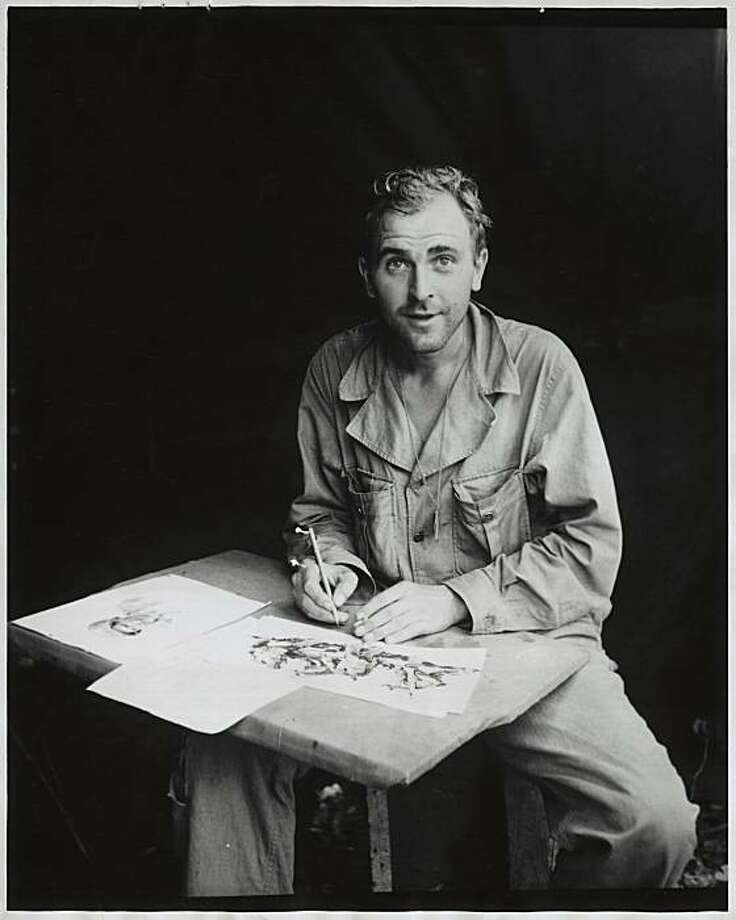

Howard Brodie: A Courtroom Sketch

-- An interview with John Turner

Howard Brodie (1915 -- 2010)

Photo: SF Chronicle Library, San Francisco Chronicle

How did you get into this field?

One of my war buddies from the Stars and Stripes newspaper, Ernie Liezer, was the vice One of president of CBS News. I remember a conversation we had where he told me “there is no place for art in television”. A month later President Kennedy was shot and Jack Ruby was going on trial, so I called him and said, “how are you going to cover it?” He said, “I don’t know, do you want to do it?” I said “yes” and went to Dallas. That’s how it started.

First Juror Max Causey during the trial of Jack Ruby 1964 by Howard Brodie

Were you the first television “courtroom sketch artist?”

I’ve been called the first television courtroom artist, but that’s not true. NBC’s Leo Hershfield was the first because he covered the McCarthy hearings. I am probably the first person to sketch a trial for television -- the Ruby trial.

How did you approach that assignment?

I had sketched a number of trials for the San Francisco Chronicle, the Harry Bridges and Tokyo Rose trials, so I had some experience. But there was no such thing as a “courtroom artist” in those days, so I was pretty much on my own.

What was your workday like during the Ruby trial?

I would usually do seven or eight sketches a day, including one that was an overall courtroom scene. At times it was unbelievable stress, strain and deadlines. When the court recessed for the day, I would run from the courtroom to the station five blocks away to get the sketches on the easel for the New York feed. Sometimes I would be putting the last stroke on sketches as they were being sent. In the Ruby trial, I was using black lithograph crayons, the same as I had used for my newspaper work. I often selected the sketches that were to be sent, but I remember the network people liking those of the courtroom spectators, as it “added to the tension of the piece.”

After the Ruby trial, what did you do next?

Eric called me again and asked if I would sketch the Senate Civil Rights debate, as they weren’t allowing cameras in. I was at the Senate for months and you had to draw totally from memory. You weren’t allowed to do one line in the building except for the written word. It was one of the best experiences I had in my life because I learned how to closely observe people.

Did this have an effect on your courtroom drawings?

Yes. Being forced to observe without drawing, one realizes that there is an essential movement or characteristic gesture particular to a person and this can be very important in depicting meaningful moments in a courtroom setting. After a trial starts, I will wait for a while to see if a person is a leaner or a dancer -- who is this person, because they speak in their own body language. People are always in motion in a trial. Sometimes subtlety on the witness stand, but they’re moving and you have to be able to draw from movement -- life as it happens. I devoted a lengthy time to learning how to do that, because there aren’t any books on that.

What other things do you look for in the courtroom?

I consider myself an artist/journalist. When I was in a courtroom, my journalist sense knew that certain subjects should be drawn, whereas in my heart as an artist, I knew that some of the great subjects were seated in “spectators row.” I tried to combine the two whenever possible. I would also try to get as much of the non- essential stuff as I could, and sublimate it into the drawings. I would also draw the judge, jury, prosecution and defense team, as well as the key witnesses, in order to form an “action library.” When I was in court, I would block my ears. I wouldn’t hear anything during a trial. I was visually focused. And I never went into a trial with an attitude or a prejudgment. I went with my feelings. What’s true commends itself. What’s false condemns itself.

What art materials did you use in your work?

I used Prisma colored pencils. They are a wonderful art pencil, come in fifty different colors, and don’t smear. My pencils were always sharpened beforehand, always. I would have maybe two hundred pencils in the courtroom, because anytime a lead broke, you can’t just stop, you have to keep going.

I finally pared my key pencils down to about a dozen, and sometimes, four or five would give the spectrum. I didn’t use erasers. Mistakes were left in the sketches. I remember being told by a reporter that a writer can always change a phrase. The writer was malleable, the artist wasn’t. For paper, I used a Strathmore Sketchpad, with a smooth but slightly textured surface.

I’ve heard you had quite a “courtroom presence.”

Well, with my pencils in my mouth and a big pad, I could be a disturbing thing to the jury. Somewhere I found some Japanese sport glasses and I used them for distance. I was a spectacle to see, but they would bring the subject I was drawing into focus from forty feet away. My fellow artist, Leo Hershfield, would always say that I was somewhat noticeable because I would get up from my seat and go over to the side to get another view. I was a wild man and Leo was very dignified.

Speaking of other network courtroom artists, how did your styles and techniques differ?

My style was heavy and more to the dramatic. Leo’s approach was light, towards the caricature. He had illustrated for Readers Digest. He worked in pen and ink and when the court had a recess for an hour or so, he would put the watercolor on. Frieda, who worked for ABC, brought pastel smears and she did it really well. Betty Well of NBC, used magic markers for her drawings. Each artist gave a whole different view of the trial, with his or her individual styles. Some would do action, while others would do characterizations of the jury. Each of us had a distinct style and vocabulary.

Being cooped up in a courtroom and away from your family for months at a time; did you get along with your fellow artists?

There was a comradeship between Frieda, Betty, Leo and myself, but there was also friction. I have a lot of respect for Frieda, but she was the terror of the courtroom. Let’s say, if the courtroom opened at ten and you wanted a good seat, she would be there at nine. If you went at nine, she would be there at eight. Frieda always got the number one seat, and if she didn’t get the number one seat, she was outraged. We were all basically in the same row, but there were better seats in that row.

Do you have any favorite courtroom stories?

I remember sketching the Manson trial. People would change during the trial. Manson would shave his head and the girls would put X’s on their foreheads. Manson was a great subject because when I was sketching him, almost intuitively he would get in a position that he would hold for me. He zeroed in on me one time and didn’t realize that he was dealing with a professional. It is my job to focus and stare. We stared at each other for a while and he was no match for me and he finally broke into a laugh.

Charles Manson seated during trial 1970 by Howard Brodie

What advice would you give to someone who wants to go into this field?

First, of all, this is no field -- never was, and never will be. I think there has been only about ten people at tops, who have made a living at “courtroom art”. A few for the network, and a few working freelance.

Any views on cameras in the courtroom?

If you want actuality, the camera shows you what’s happening in the courtroom. If an artist is expressive, they can offer a human dimension. I think it’s better to have the actuality than the artist. I know I was a substitute for a camera and that’s a demeaning thing. The artist does have a place in television.

What do you think about art in general?

I think art is expressionistic. I try to capture what I feel. I think art, if it has any meaning at all, is getting the inside out. The best work I do is when I don’t know what I’m doing. There is no eye involved. It’s a state of being within.

Do you have a favorite artist?

I have many, but I especially like Cy Twombly. He’s a real thriller to me. He really manifests the state of being of a human.

Please post your comments to John's Profile page at OkemosAlumni.org